Introduction

In the field of animal biology and dairy science, digestion is among the most vital processes to comprehend especially when it comes to ruminants like cows. A cow’s digestive system is far more complex than that of monogastric animals (like humans or pigs) due to its multi-chambered stomach, specialized microbial environment, and ability to extract nutrients from fibrous plant materials.

Understanding how this system works is key not only for veterinarians and farmers but also for researchers studying sustainable agriculture, methane reduction, and milk production efficiency. This article explores the cow digestive system in detail breaking it down by each organ, analyzing nutrients, and providing comparisons with other species. Whether you’re a student or a professional in livestock sciences, this updated 2026 guide is built to inform and inspire.

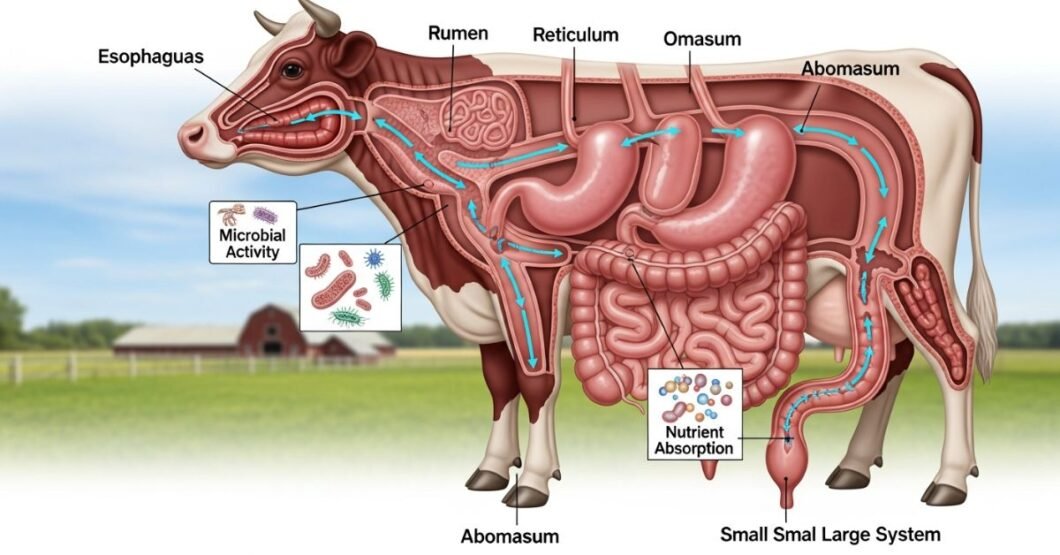

Overview of the Four Compartments in a Cow’s Stomach

Cows are ruminants, meaning they have a unique, four-chambered stomach designed to digest tough plant matter. Each compartment plays a different role:

The Four Chambers:

- Rumen: Ferments feed with microbes

- Reticulum: Sorts and regurgitates particles for rumination

- Omasum: Absorbs water and minerals

- Abomasum: Functions similarly to a human stomach, digests proteins

Chamber Primary Function Enzymes/Agents Involved Rumen Microbial fermentation Bacteria, protozoa Reticulum Particle sorting Saliva, microbes Omasum Moisture absorption Water channels Abomasum Protein digestion Pepsin, HCl

The synergy among these compartments supports the cow’s ability to process cellulose and turn low-energy feeds into high-energy products like milk and meat.

The Rumen Microbiome: The Engine of Fermentation

The rumen, the largest of the stomach chambers, acts as a fermentation vat. It hosts billions of symbiotic microbes that break down fibrous plant material.

Microbial Breakdown Process:

- Cellulose and hemicellulose are digested into volatile fatty acids (VFAs).

- Gases like methane and CO₂ are released during fermentation.

- VFAs serve as the cow’s primary energy source.

Component Microbial Agent ByproductCellulose Fibrolytic bacteria Acetate + Methane Sugars Amylolytic bacteria Propionate Proteins Proteolytic bacteria Ammonia/Nitrogen

Maintaining a balanced rumen pH between 6.0 and 6.8 is vital for fermentation consistency, feed efficiency, and bloat prevention.

Reticulum and Rumination: A Built-In Chewing Regulator

Located near the heart, the reticulum works closely with the rumen and is responsible for sorting food particles by size.

Function of the Reticulum:

- Traps indigestible material (e.g., metal, sand)

- Initiates the rumination process a cycle of regurgitation, rechewing, and reswallowing

Interesting Fact: The honeycomb texture of the reticulum traps foreign objects, a reason cows suffer from “hardware disease” if ingesting metal accidentally.

Action Time per Day (avg) Purpose: Rumination 6–8 hoursParticle size reduction Saliva production Up to 150 L/day Buffer rumen pH

Rumination improves feed digestibility and reduces acidosis risk both crucial for herd health and productivity.

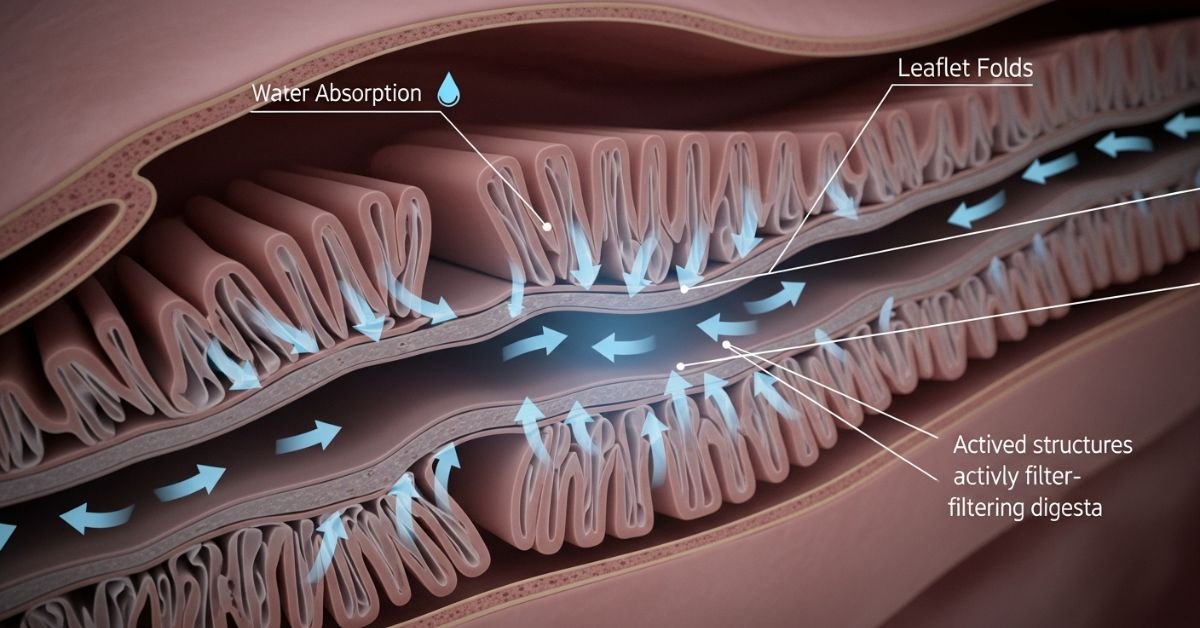

Omasum: Filtering and Water Regulation

The omasum acts as the “sponge” of the cow’s stomach, filtering out large particles and absorbing water and minerals.

Its Major Functions:

- Transport of small particles to the abomasum

- Absorbs volatile fatty acids and electrolytes

- Decreases dilution of future digestion

The omasum features broad, layered folds (like pages in a book) that maximize its filtrating surface area.

Nutrient Absorbed Area in Omasum Benefit to System Sodium + Potassium Leaflet membranes Regulates muscle function VFAsPapillae structures Energy recovery

Although less dynamic than the rumen or abomasum, the omasum plays a gatekeeping role that ensures only well-processed food moves downstream.

Abomasum: The Cow’s True Stomach

This is the only gastric compartment in ruminants that resembles a human stomach. It comprises the acid-secretory region responsible for actual digestion via enzymes.

What Happens in the Abomasum:

- Hydrochloric acid (HCl) breaks down food.

- Enzymes like pepsin start protein digestion.

- Kills remaining bacteria not absorbed in the rumen

Digestive Component Produced EnzymeTarget NutrientChief Cells (lining) Pepsin Proteins Parietal Cells HCl bacterial mass

A twisted abomasum can be fatal, disrupting digestion and requiring surgical correction common in high-producing dairy cows.

Nutrient Absorption in the Small Intestine

After food passes through the abomasum, it enters the small intestine, where most nutrient absorption occurs.

Small Intestine Functions:

- Final breakdown of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins

- Absorbs vitamins, amino acids, fatty acids

- Uses enzymes like lipase and trypsin

SectionFunction Duodenum Receives bile, neutralizes pH Jejunum: primary nutrient absorption Ileum: Vitamin B12 absorption, waste transfer

A well-functioning intestine not only supports energy metabolism it correlates with immune system health and reproductive success.

Waste Conversion and Fermentation in the Large Intestine

Though not as essential as the stomach chambers, the large intestine contributes to fiber breakdown and waste formation.

Primary Roles:

- Water recovery and drying of digesta

- Small fermentation chamber via microbiome

- Prepares feces for excretion

Roughly 12–15% of energy from feed can still be salvaged here—especially in high-fiber diets like silage or haylage.

FunctionOrgan LocationEfficiency Boost Water Balance Colon: 90% absorption Nitrogen Recycling Cecum immune health

Large intestine fermentation although limited adds unnecessary microbial waste if the process upstream is impaired.

Digestion Timeline: How Long It Takes to Process Feed

Cows spend a significant part of their day digesting, grazing, chewing cud, or resting.

Processing Time Required Rumen fermentation 24–48 hours Protein absorption: 1–2 hours per cycle Total emptying: up to 80 hours

Fun Fact: A single meal could take over 3 days to completely pass through the cow digestive system depending on diet quality.

Multiple ongoing processes mean cows are almost always digesting, particularly in high-yield operations.

Impact of Diet on Digestion Efficiency

Different feed types affect digestion time, gas production, and VFA output.

Feed TypeRumen pH Impact Digestion Speed Fresh Forage Neutral (high) Slower Grain-heavy Acidic (low) Faster Silage Slightly acidifying Moderate

High-concentrate diets might boost milk output but raise the risk of acidosis. Balanced formulations allow microbial populations to thrive while avoiding dysfunction.

Future of Nutritional Engineering in Cow Digestion

The use of digestibility enhancers and biome trackers is growing.

Innovations to Watch:

- Rumen boluses to monitor pH, temp, and gas

- Pre- and probiotics to support gut flora health

- GMO feeds engineered for high digestibility and lower methane output

ToolGoalpH Monitors Prevent acidosis. Smart Sensors Optimize forage digests additives. Reduce methane emissions.

As climate metrics become linked with livestock production, the study of the cow digestive system plays a key role in sustainable farming.

FAQs

Why does a cow need four stomachs?

Each chamber specializes in breaking down fibrous plants, maximizing nutrient absorption.

What happens if digestion is impaired?

It can cause bloating, acid imbalance, poor nutrient uptake, or even fatal digestive disorders.

How long does rumination last each day?

6–8 hours on average.

Do all ruminants have the same digestive system as cows?

They are similar, though size, volume, and microbial composition vary.

Can diet influence methane emissions in cows?

Absolutely. Specific ingredients and probiotics can reduce emissions by supporting better microbial balance.

Conclusion

The cow digestive system is a marvel of evolutionary efficiency engineered to extract energy from cellulose-rich feeds that monogastric animals simply can’t digest. Each compartment, from the rumen to the abomasum, plays a specialized role in supporting not just survival, but high-level productivity like milk and meat generation.

In today’s push for sustainable agricultural systems, mastering cow digestion goes beyond biology it enables innovation, environmental care, and food security. So whether you’re designing feed, monitoring herd health, or studying digestive physiology, this unique system remains one of biology’s most fascinating examples.